We know feedback matters. I think of all the ways I have grown because my students, my husband, my editor, and so many others have bothered to share their wisdom with me. Sometimes it stings. Sometimes it sits in the back of my mind, waiting for the right moment. And sometimes, it changes everything.

And yet, when it comes to students, we often act as if feedback is something we do to them rather than with them. We spend hours writing comments, circling errors, suggesting revisions. But how often do students actually use it? How often does our feedback feel more like judgment than guidance?

Maybe it’s time to rethink who gives feedback, how it’s given, and why it even matters. And maybe we can shift our feedback practices in ways that actually work for kids—without adding more to our plates. Here are four shifts that put students in charge of their own growth.

1. Ditch the Teacher-Only Feedback Model

We shouldn’t be the only ones giving feedback. In fact, we might be the worst at it—too rushed, too generic, too focused on what we think matters instead of what they care about.

💡 New idea: What if students got more feedback from peers, younger students, real-world audiences, and even AI tools—and less from us?

👉 Try this:

- Have students share their writing with a younger class. It’s wild how quickly they’ll simplify, clarify, and revise when they realize a first grader is their audience. I have done this for years with speeches and even our nonfiction picture book unit, it alters the entire process.

- Use AI to generate feedback alongside human feedback—then have students compare. What’s useful? What’s missing?

- Create a “feedback portfolio” where students collect and analyze all feedback received (not just yours) and decide what’s worth acting on.

2. Scrap the Grade—But Not for the Reason You Think

We talk about “going gradeless” to reduce stress, and to make learning more meaningful, but removing grades doesn’t matter if students still see feedback as punishment.

💡 New idea: It’s not about eliminating grades—it’s about making assessments feel like coaching instead of judgment.

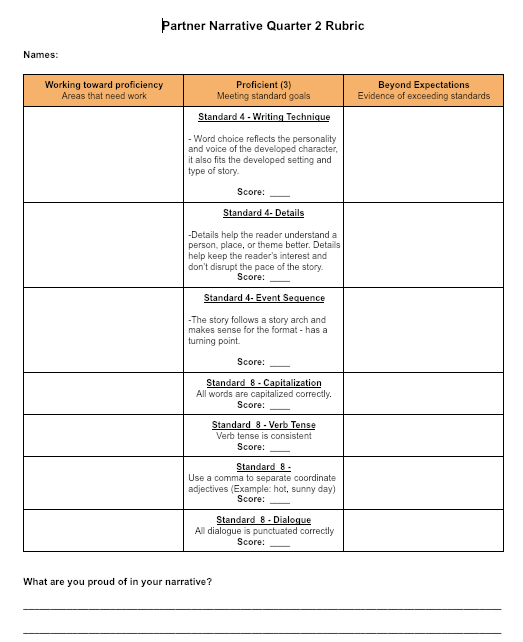

👉 Try this: Instead of “no grades,” try collaborative grading. Sit down with a student and decide their grade together based on evidence of growth. Let them argue their case. Shift the power.

I have done this for many years, not just with student self-assessments but also their report cards. The conversations you end up having as a way to figure out where to land offer immeasurable insight into how kids see themselves as learners.

3. Let Students Give YOU Feedback First

What if every piece of feedback we gave students had to start with them giving us feedback first?

💡 New idea: Before turning in a project, students answer:

- “What’s the best part of this work?”

- “Where did I struggle?”

- “What specific feedback do I want from you?”

👉 Try this: Make a rule: no teacher feedback without student reflection first. If they can’t identify a strength and a challenge, they’re not ready for feedback yet.

4. The One-Word Feedback Challenge

Ever spend time crafting detailed feedback, only to have students glance at the grade and move on?

💡 New idea: What if our feedback had to fit in one word? Instead of writing long paragraphs that students ignore, we give a single word that sparks curiosity: Tension. Clarity. Depth. Risk. Precision.

👉 Try this: Give students one-word feedback and make them consider what it means. Have them write a short reflection: Why did my teacher choose this word? How does it apply to my work? This forces them to engage with feedback before receiving explanations.

Feedback shouldn’t feel like a dead-end—it should be a conversation. When we shift the balance, when students take ownership, feedback stops being something they receive and starts being something they use. And isn’t that the whole point?