“This is not a “girl” book even if the cover makes you think it is, boys can love it too…”And I stop myself. And I cringe inwardly. And I want to rewind time for just 10 seconds and tell myself to stop. A “girl” book? What in the world is that? And since when did I label our classroom books by gender?

The stereotypes of reading seems to be a beast in itself. We feed the beast whenever we pass on hearsay as fact. We feed the beast whenever we fall victim to one of these stereotypical sayings without actually questioning it. Through our casual conversation we teach our students that there are books for girls and books for boys. We teach our students that a strong reader looks one way, while a struggling reader (God, I hate that term) is something else. We say these things as if they are the truth and then are surprised when our students adopt the very identities we create.

So what are the biggest myths that I know I have fed in my classroom?

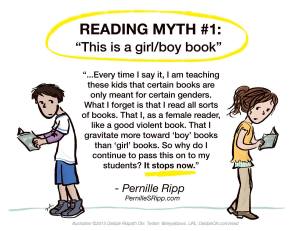

“This is a girl/boy book.” I have said this many times as I try to book talk a book. I say it when I think the boys, in particular, will not give a book a fair chance because of its cover. I say it when I think the girls will find a book to be too violent, to have too much action. And every time I say it, I am teaching these kids that certain books are only meant for certain genders. What I forget is that I read all sorts of books. That I, as a female reader, like a good violent book. That I gravitate more toward “boy” books than “girl” books. So why do I continue to pass this on to my students? It stops now.

“This is an easy read.” Another common statement I have made while book talking. What I mean by it is that for most students the text will not prove difficult to understand, yet I know now that ease of reading looks very different from student to student. That what I may think is easy, even when I pretend to be a 7th grader, is not easy at all. That even if a book is short does not make it easy. Even if a book has a manageable story line does not make it easy. That “easy” means different things to different readers and therefore does not provide a good explanation to anyone. It stops now.

“He/she is a low or high reader.” Our obsession with classifying students based on their data does not help our students, it only helps the adults when we are discussing them. There is an urge in education to group kids according to data points so that rather than take the time to discuss each student, we can discuss them as a group. Yet the terms “low” or “high” make no sense when discussing readers. They make sense when we are discussing data points, but is that really all our students are? How many of us have taught students who were amazing readers, yet scored low on a test? What would we call them? We need to discuss students using their names and their actual qualities, not these shortened quantifiable terms that only box them in further. It stops now.

“Most boys don’t really like to read.” I don’t know how many years of teaching boys I need to finally stop saying this. Many boys like to read – period – but when we say that most don’t, we are telling them that what they love is not a masculine thing to do. That boys loving reading is something strange and different. If we want this to come true, we should just keep repeating this over and over. Our male readers will soon enough get the message that reading is for girls. It stops now.

“The older they get, the less they love books.” I used to believe this, until I started teaching middle school. Then I realized that it is not because students want to read less as they get older, they read less because we have less time for independent reading, and we dictate more of their reading life. Homework builds up as do other responsibilities outside of school. Compare a 5th grader who has 30 minutes of independent reading most days to my 7th graders that get a luxurious 10 minutes – who do you think reads more in a year? Also, I wonder if anyone would want to keep reading if they did not get time for it in school or had choice over what they read for several years? Sometimes I think it nearly a miracle that students’ love of reading can survive what we do to them in some educational settings. It stops now.

“But they are not really reading…” I used to be the hawk of independent reading, watching every kid and making sure that for the entire time their eyes were on the text. If they stopped I was there quickly to redirect. Independent reading time was for independent reading and by golly would I make sure that they used every single second of it. Yet I don’t read like that myself. When I love a book, I pause and wonder. When I love a book, I often look up to take a break, to settle my thoughts. When I love a book, my mind does not wander but I still fidget. That doesn’t need a redirection, that doesn’t need a conversation, that simply needs to be allowed to happen so I can get back to reading. Our students are not robots, we should not treat them as such. Re-direct when a child really needs it, not the moment they come up for air. It stops now.

“They are too old for read alouds…picture books…choral reading…Diary of Wimpy Kid…” Or whatever other thing we think our students are too old for. No child is too old for a read aloud. No child is too old for picture books. No child is too old for choral reading. No child is too old for books like Diary Of A Wimpy Kid. Perhaps if we spent more time showcasing how much fun reading really is, kids would actually believe us. It stops now.

The myths we allow ourselves to believe about reading will continue to shape the reading lives of those we teach. We have to stop ourselves from harming the reading experience. We have to take control of what we say, what we do, and what we think because our students are the ones being affected. We have a tremendous power to destroy the very reading identity we say we want to develop. It stops now. It stops with us.

If you like what you read here, consider reading my book Passionate Learners – How to Engage and Empower Your Students. The 2nd edition and actual book-book (not just e-book!) comes out September 22nd from Routledge.

When students are labelled “fast” or “slow” readers…ugh! They are readers!

Here, here, very well said. I especially have to remind myself about the “not REALLY reading” and what message I am sending. Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

Amen! And yet…I catch myself talking this way al the time. Thanks for the reminder, Pernille.

Hi Pernille,

So much truth here.

You mention you hate the term “struggling reader.” Curious to know what works better. There are students who struggle with reading due to decoding, automaticity or fluency issues. Others may be learning a new language. The process of reading is more challenging and we have to acknowledge that reality. Too often, they have learned to dread reading. Is there a better term?

Yes, “developing” reader works much better because it is a much more accurate term to describe what they are doing. I blogged about it here as well https://pernillesripp.com/2015/06/25/my-child-is-not-a-struggling-reader/

Thanks for your quick response. I remember reading that post, Pernille.

But what do we say when they are in middle or high school and still “developing?” I think acknowledging the struggle is essential (I know, my son was (and is, still, at 24) a struggling reader. He has learned how to bypass his reading challenges using technology. At some point, it is no longer “developing.” Not sure when that transition occurs. But, despite intensive remediation, some students still struggle with reading. Developing just doesn’t seem to apply for all situations, especially when working with students with reading goals on their IEPs.

This is inspiring me to write a new post on the term! I do think that the struggle with reading should be acknowledged, but I think it is a bad idea then to take the term and create a label for a reader with it. Yes, learning to read well can be a struggle, but becoming a struggling reader means that every single moment is a fight to the end. That you struggle through every single thing. I don’t think that is a good connotation to give to any readers and neither is “developing” for that manner. They are readers, why the need for further labels when we speak about them as a child?

Because they no longer see themselves as readers.

What has happened along the way? I work with too many students who “hate” reading (due to their reading challenges). It breaks my heart. They choose to avoid reading at all costs. (have you ever seen the student who struggles with reading suddenly need to go to the bathroom when it is their turn to read outloud in their small group?)

This is an important topic to me as an assistive technology specialist. I want to remove the struggle so that students who do not see themselves as readers can enjoy books and what is possible. Acknowledging that reading is difficult for many students can remove the stigma and help them realize there are ways to make reading easier and less of a struggle.

I appreciate your comments. I don’t want any students graduating from high school saying they will never read another book (like my son did six years ago. Fortunately, he now uses technology and has read many self-selected books in the past three years).

This is great and really pushing my thinking and I think your first sentence is exactly the reason why we shouldn’t be labeling them further. If they don’t seem themselves as readers then that is the very first thing we work on, I would never then tell a child in that position that they were a “Struggling reader.” That doesn’t mean I would dismiss their effort or struggle, just not put the label on them.

I think we really are speaking the same language. I never tell a student that they are struggling reader. I may describe them in that manner when I’m at an IEP team meeting. And I may talk with them about how they struggle with reading or how reading might be challenging to them. But I don’t tell a student that that is their label.

Acknowledging the struggle and labeling them to their face as a struggling reader are two very different things.

Wisdom. Thank you.

My four year old nephew slept over last week and as I was putting him to be I read a picture book to him. My eleven year old son asked for another picture book when the first was done. I read chapter books to him every night as part of our bedtime ritual, but I haven’t read him a picture book in years. I guess I forgot how great they can be! I will add them back to our bedtime reading list.

All my years working in the library and doing reader’s advisory I come across the same hesitancy in regards to “girl books and boy books.” More often than not, the hesitancy is by the mom not wanting her son to read a “girl book.” The kid doesn’t care, the dad’s don’t care. But its the mom that I can’t get through and that’s the frustrating part. Good stories are good stories, why does it matter if its a girl or boy protagonist? Its usually the moms who define books in that way and it drives me bonkers. I have a toddler at home, and I constantly bring home books with female characters for him. Mostly because these are the only books that deal with social etiquette and aren’t just about trucks and sports. Its sad seeing how gendered picture books are, from a librarian and mother’s perspective. This unnecessary division starts so early in their lives from how they see gender stereotypes portrayed in books.

I simply can’t resist commenting here. Thank you for articulating the multiple, often offhand ways we diminish the reading experience for students. As a parent of a reader who loves book after book and cannot read independently yet, this conversation is top of mind. He loves being read to and it can be a challenge not to over-intervene and push the sight words and skill building which he quickly experiences as a chore. Keeping the end goal in mind: to develop and nurture an enthusiastic reader, is a priority I sometimes struggle to maintain in order to avoid that label “struggling” which becomes the short-term game to win.

Reading is so much more than decoding and my son is here to remind me of that. Your post and the insightful comments that follow offer encouragement and bolster my patience.

As an avid reader, novelist, an early reader (preschool) who has observed child and adult readers for decades…this post gets a “Brava!” from me. I know people who had difficulty reading who stopped trying when told “You’re too old to read horse books/baseball books/picture books.” Yet the woman who quit trying in school continued to read horse magazines and horse books, including making it through the highly technical English translation of Alois Podhajsky’s master work on horse training. I read boys’ books mostly because I liked action and adventure (not necessarily violence–but definitely excitement.) While in graduate school I tutored kids who were having difficulty in middle and high school–mostly in science and math, but a few in English. Every time a teacher or librarian suggests that a book is too young, too old, too easy, too hard, too whatever–a child’s innate desire to read takes a hit. Not only are there no girl books or boy books, there are no X-grade books (the way the town library was divided when I was a kid), no “children’s” or “teen” books.

My mother argued with the town librarian and freed me from the rigid grade-level limits when I first complained that I couldn’t check out the horse book I wanted because it was on the third-grade shelf. By the time I was eight, and had finished all the books in the children’s room I wanted to read, she argued again and got me an unrestricted library card. Sure, lots of books for adult were beyond me…I dipped into them, found them boring-for-now, and opened another. But if they were on a topic that interested me (horses, airplanes, rockets, exotic places, dinosaurs, astronomy) then I stretched my brain to learn. When I was in college, a friend whose younger brother was “struggling” with reading asked him what he wanted to read about. Pirates, he said. She gave him a book about pirates; his supposed struggle with reading vanished in two weeks. He’d been bored stiff reading those carefully designed books for readers with problems. (He’s now a scientist.)

Some children like fantasy; some don’t. (I didn’t, then. I didn’t like fantasy until college, and now I write it.) Trying to pull a child away from enthusiastically reading about what interests the child (whatever that is) because he/she “should” like something different assumes that some books are healthier vegetables and others are less healthy popcorn. Maybe true for candy v. carrots, but it’s not true with reading skills, literacy, and long term development of literate adults who still enjoy reading for pleasure. Let kids explore the book-worlds that fascinate them; let them gather in interest groups to discuss their favorite books (We didn’t do that in school, but we did at recess, holding mini-literary panels on horse books or sports books or mysteries.) Look at how kids discuss the Harry Potter books–arguing about plot points, characterization, themes. Free reading–independent reading–reading without having to justify and analyze to a grownup–leads to adults for whom reading is a lifelong joy.

Reblogged this on The Joyful Reader and commented:

Loved this.

Reblogged this on Memórias ao Vento.