We have been studying genres in 3rd grade.

Something so simple, and yet such a powerful key to unlocking yourself as a reader. For some students, these classifications are crystal clear; they already have the language that wraps around them as readers. For others, the designations are murky at best—confusion between fiction and nonfiction (which I completely understand in this day and age), and even what it means for something to be a genre at all.

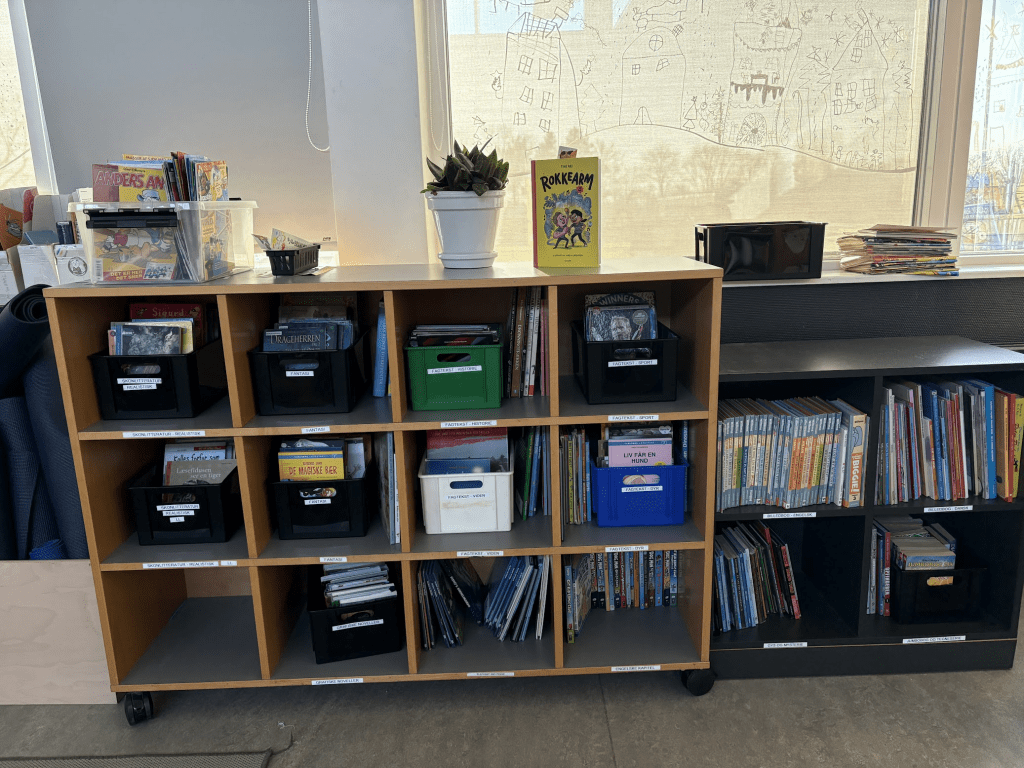

It’s also a practical challenge: how do we turn a messy classroom library into something students can actually navigate? Sorting books by genre is a powerful way for students to deepen their understanding of different types of texts and make the library itself more accessible. It is something I have believed in for years.

And so, we persisted in the work. We sorted texts and discussed what makes something realistic fiction, fantasy, horror, or nonfiction. What separates fantasy from a scary story? How do we know realistic fiction isn’t just fantasy in disguise? Their questions were legitimate, and they shaped the work we did.

To truly see their comprehension in action, we turned to our modest classroom library. Those who have followed my work from before my move to Denmark may remember my vast classroom collection—books spanning walls, even rooms. I left that library behind for the teacher who took over my classroom, knowing it would have more use in the United States than it would here.

But that also meant starting over.

Books in Denmark are expensive—often more than 200 kroner (around $20) even for an easy reader. Classroom libraries are not seen as a priority. School libraries aren’t either in some places. So building a collection has been slow, relying on goodwill finds, donations from our amazing librarian and some families, and a few contests won along the way. It is nothing impressive. It may never be. But it is real, and it reflects the reality of many educators.

And it is a place to start.

I teach two 3rd-grade classes in Danish: one I have been with since 1st grade, and another added this year. With my “old” class, the task was simple. After our genre lessons, I introduced the project: let’s sort and categorize our classroom library using the knowledge we now have. We decided on which genres and even subgenres we thought we would have, discussed their abbreviations and then launched into the process itself; I would hand them piles of books, they would sort them by the genre or format they believed they belonged to by creating piles on tables, I would create labels, and together we would shelve them.

It took two lessons, but by the end our classroom library was mostly sorted correctly, and the students were eager to dive back into books they had discovered along the way.

Buoyed by this success, I brought the same process to my new class. I knew they might need a little more guidance, but surely my well-planned lesson would be successful.

It was not.

It was frustrating, confusing, and messy—and through no fault of the children. They tried their very best to figure out what we were doing and to do it well, as they always do. But the pieces they needed simply weren’t there yet.

So I took time over the weekend to think it through and quickly recognized my mistakes. They needed far more scaffolding. They needed the work to stop feeling like a competition over who could get through the most books. They needed to lean on each other for guidance. They needed explicit permission, as always, to ask questions and to not be sure out loud.

On a day when I knew I had them for three periods in a row, I knew we could afford to get messy. I reintroduced the concept and explained the new plan.

Two students, who seemed to have genre determination skills firmly in place, sat at the lead table. Their job was to decide whether a book was fiction or nonfiction and to venture a guess at its genre or format (graphic novels and comics were sorted onto their own shelf). They passed their books to three other students, who double-checked the decision and delivered them to the appropriate genre table. Each genre table was staffed by a student whose job was to agree—or disagree—and send the book back if needed.

I placed students based on their perceived strengths within a genre. Some worked alone. Some sat near related genres so they could support one another. And then we began.

At first, there was hesitation. Were they really sure that a certain book belonged in a certain genre? How could they even tell again?

But as the process continued, their confidence grew. Their decisions became more certain. Help was offered more freely. It was still messy. It was still a bit chaotic. But the process worked.

Not because I taught it better—but because I reconsidered my scaffolding. I reconsidered the conditions. I stepped away from my own attachment of feelings to a lesson—failure—and recognized that this, too, was success: realizing, once again, what didn’t work and adjusting the conditions., with the only failure being to not do it again.

In the end, this wasn’t really about genres, or even about sorting a classroom library the “right” way. It was about slowing down enough to notice where my teaching had raced ahead of my students, and choosing to meet them where they actually were. Understanding didn’t come from efficiency or speed, but from time, conversation, and the safety to be unsure out loud.

The messiness didn’t disappear when I changed the structure.

The noise didn’t go away.

But what did change was who carried the thinking. Students leaned on each other. They questioned, disagreed, and revised their ideas together. And in that space, comprehension began to take root.

We now have a tiny little classroom library, where the gaps in what we don’t have are stark, and yet the hope of finding books to read feels big. Students get to look at the bookstacks and decide which books to keep and which to let go.

It’s a small piece, but one that further cements their identity as readers—students who now know that if they understand the genres they enjoy, they can seek out those books first. Students who have taken a big step toward knowing who they are, and perhaps even more importantly, who they want to be as readers.

It may have taken longer than expected. It may have veered off course. But those hours spent were hours I know were worth it.

So for now, the reading continues.